In this monthly series reviewing classic science fiction books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of science fiction; books about soldiers and spacers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

The authors of the Golden Age of science fiction, and their works in later years, were indelibly shaped by World War II. Many served in the Armed Forces, while others worked in laboratories or other support functions—Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, and L. Sprague de Camp, for example, worked together at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Time passed, and in the 1970s a novel appeared, The Forever War, which was written by newcomer Joe Haldeman, a member of a new generation who was shaped by a very different war. The book, with its bleak assessment of the military and warfare in general, had a profound impact on the field. And today, as more and more people refer to our current conflict with terrorists as the Forever War, the book’s viewpoint is as relevant as ever.

Regarding writing, Samuel L. Clemens is quoted as saying, “The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter—’tis the difference between the lightning-bug and the lightning.” If you put together enough of the right words, in all the right places, you can produce a novel that has the impact of a lightning bolt. That is exactly the impact The Forever War had on me. I was in my third year at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy, and bewildered by the social changes I was seeing in the country around me. I had joined up in the waning days of the Vietnam War, and even though they were no longer drafting people, I still remember my draft number being picked. We had all watched the helicopters carrying our embassy staff out of Saigon, our last involvement in a demoralizing conflict. To go out in public in a uniform, or even with just a military haircut, could draw insults like “fascist” and “babykiller.”

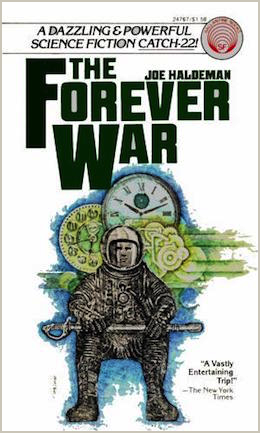

To many people, serving in the military was no longer an honorable profession. The gung-ho military adventures I had read in my youth had not prepared me for this. But I still had an interest in military science fiction, so when I saw a paperback edition of The Forever War in a local bookstore, I snapped it up. It had a man in a spacesuit on the cover, surrounded by old timepieces and with a saber across his lap (at the time, I thought the sword was as symbolic as the clocks, not realizing it would play a role in the tale). I remember reading it in large gulps, and feeling throughout that this Haldeman guy really knew what he was talking about. And I was not alone. The book sold very well, was critically acclaimed, and won both the Nebula and Hugo awards.

Background: The Vietnam War

War came to Vietnam in World War II and continued in the wake of that conflict, as the local population revolted against French colonial rule. The French withdrew, leaving the nation split between NATO-supported South Vietnam, and communist Russian and Chinese-supported North Vietnam. U.S. involvement in the war between North and South Vietnam began in the 1950s but escalated significantly in the 1960s, with advisors and military aid giving way to regular troops, and significant air and naval campaigns. The draft was re-instituted to meet demands for troops.

At the same time as the war effort was ramping up, the U.S. found itself in a time of internal turmoil and spiritual re-awakening. The younger generation was questioning old truths, and experimenting with drugs and alternative religions and philosophies. The draft was a polarizing force in society, and many people, especially younger people, turned against the war, and the military in general. This made the homecoming of veterans very difficult, as they were already demoralized by their service in a bloody and difficult struggle, and were often treated with derision and contempt upon returning to the U.S.

U.S. involvement in the war peaked in 1968, around the same time as the North and the Viet Cong insurgents launched the Tet Offensive. While inconclusive militarily, the widespread attacks undercut Department of Defense arguments that the U.S. had been successful in destroying the enemy’s military capabilities, and support for the war among the American public dropped significantly. A peace treaty was signed in January 1973, and U.S. military involvement ended in August 1973. Saigon was captured by the North Vietnamese Army in April 1975, and the evacuation of the U.S. embassy marked the ignominious end of a divisive conflict.

About the Author

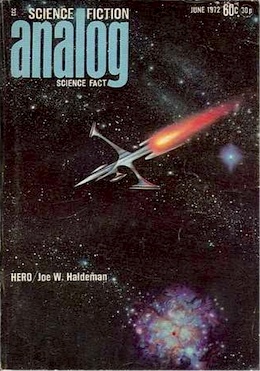

Joe Haldeman (born 1943) graduated from the University of Maryland with a BS in astronomy in 1967. Shortly after that, he was drafted into the U.S. Army, and despite personal concerns about the morality of war, he served from 1968-9 as a combat engineer in Vietnam’s central highlands. Wounded in an incident involving unexploded ordnance, he returned home with a Purple Heart. He had always wanted to be a writer, and received early encouragement from Damon Knight’s Milford Writer’s Workshop, and specifically from Ben Bova, who was also in attendance. Bova had encouraged Haldeman to write fiction based on his wartime experience, which led first to a mainstream novel, War Year, and then to the science fiction novel The Forever War. When he succeeded John Campbell as editor of Analog Science Fiction, Bova purchased the story, and it appeared in four Analog installments from 1972 to 1975, and was published as a standalone novel in 1975.

The Forever War, besides winning both the aforementioned Hugo and Nebula awards, started a long and distinguished career for Joe Haldemen. He went on to win six more Hugos and four further Nebula awards for later novels, novellas, and short stories. He was elected a SFWA Grand Master and a member of the SF Hall of Fame. Haldeman is a consummate professional, whose focus is writing what he is passionate about, rather than simply to earn money. He is a fan of Ernest Hemingway, and it shows in his prose, which is crisp and carefully crafted. By all accounts he is generous to his fellow writers, and I know from personal experience that he is generous to fans, as is his wife Gay. At my father’s insistence, my introduction to fandom and WorldCon was a “How to Attend a Con” panel co-hosted by Gay and long-time fan Rusty Hevelin, and I remember interactions with Joe as highlights of an event that was packed with special moments.

The Forever War

The book starts in 1997, following the military career of William Mandella, a child of hippie parents who has been drafted under the Elite Conscription Act. The human race has discovered that links between collapsars are the key to long range travel around the galaxy, but mankind soon encounters a mysterious race they call the Taurans, ships are lost, and a punitive expedition is planned. The personnel picked for the United Nations Exploratory Force (UNEF) are not only sound of mind and body, but all have IQs of at least 150. The force mixes men and women, encourages sex between them, allows the use of marijuana, and considers “Fuck you, sir” as the appropriate response to an order to come to attention. Because of the distance of travel to get to collapsars, even at relativistic speeds, missions will be measured in months, if not years—and that is the objective time experienced by the travelers. Back home, because of relativity, the length of the missions will be measured in years and decades.

The book starts in 1997, following the military career of William Mandella, a child of hippie parents who has been drafted under the Elite Conscription Act. The human race has discovered that links between collapsars are the key to long range travel around the galaxy, but mankind soon encounters a mysterious race they call the Taurans, ships are lost, and a punitive expedition is planned. The personnel picked for the United Nations Exploratory Force (UNEF) are not only sound of mind and body, but all have IQs of at least 150. The force mixes men and women, encourages sex between them, allows the use of marijuana, and considers “Fuck you, sir” as the appropriate response to an order to come to attention. Because of the distance of travel to get to collapsars, even at relativistic speeds, missions will be measured in months, if not years—and that is the objective time experienced by the travelers. Back home, because of relativity, the length of the missions will be measured in years and decades.

The UNEF has decided that bases are needed on planets around the collapsars, to defend against enemy incursions; because these planets will be cold, the troops are trained out on Pluto and beyond, where the environment is more dangerous than enemy action. They are trained to operate in powered armor suits, to build bases and weapon systems, and in personal combat, should that be required. Despite his misgivings about the military, Mandella has a knack for leadership, and soon finds himself promoted to corporal. He also finds himself developing a friendship with fellow trooper Marygay Potter.

Their training for operations in extreme cold turns out to be premature, as their first mission takes place under different conditions. They are sent to attack an existing enemy base on a planet near the Aleph Aurigae collapsar. Since that collapsar orbits around the star Epsilon Aurigae, the conditions they fight in will be more in the range of those found on Earth. Approaching their destination on the ship Earth’s Hope at two gravities of acceleration, the troopers destroy both an enemy vessel and the missile it launched against them. On the march to the enemy base, they notice the planet’s odd ecology, and soon find their force shadowed by alien creatures. They kill and dissect them, and from the contents of their stomachs, find that they are local herbivores.

One of the soldiers dies of a massive cerebral hemorrhage, and it seems that the bear-like creatures use some sort of telepathic communication. They see a Tauran flying by in a bubble-like craft, a creature with two arms and two legs, but otherwise not human in appearance at all. When they have the enemy base surrounded, their sergeant quotes lines of poetry that trigger post-hypnotic suggestion, and the team destroys the base and butchers its inhabitants. In the end, though, more troopers are hurt by the psychological impact of the post-hypnotic suggestion than the enemy, and one of the enemy escapes in a ship to bring word of what has happened to the Taurans.

The team then finds themselves sent on the ship Anniversary to another campaign near the collapsar Yod-4. Mandella is now a sergeant, and Potter a corporal, and their relationship has grown closer. While they have experienced only two subjective years aboard ship, over two decades have elapsed for the rest of the universe, and technology on both sides of the conflict is advancing in leaps and bounds. The Taurans are pursuing their ship, and the team retreats to newly developed acceleration shells, designed to protect them while this more advanced ship accelerates at up to 25 gravities. They find that the enemy now has drones that accelerate at over 200 gravities, and they retreat to their acceleration shells for evasive action. Potter’s acceleration shell fails, and she is badly injured and near death. Their ship has been damaged, destroying their armored suits and killing many troops. They have no choice but to return to base, and the survivors are sent back to Earth.

At this point, different editions of the book vary significantly. The original version I purchased in 1976 focuses largely on Mandella and Potter’s experiences on a military public relations tour, as well as visiting his family. The Earth has not fared well in the years they have been gone; the population has grown significantly, to the extent that homosexuality is now actively encouraged as a population control measure. The Earth can barely feed its inhabitants, and getting enough to eat is a daily worry. Crime is rampant, and Mandella is horrified to find that medical resources are rationed—his mother is dying because she has not been approved for treatment. Disgusted with what they see, Mandella and Potter accept the military’s offer to return to duty with officer’s commissions. More recent editions of the book restore Haldeman’s original text, however, which depicts a much longer time on Earth, with a visit to Potter’s family showing the brutal conditions on a farm country commune. While this does stray from the military theme of the book, I find the longer interlude is more satisfying, as it not only deals with the alienation the troops experience upon returning home, but also provides a more convincing motive for the protagonists’ return to the horrors they have experienced in combat.

The book then covers Mandella and Potter’s service as lieutenants, a time of brutal and inconclusive struggles that ends with both in the hospital, wounded and with lost limbs. They think this will be the end of their military careers, but it turns out that limbs can now be regrown, something they hadn’t realized was possible. While time passed quickly for them due to time dilation, this period covers over three hundred years of objective time, and humanity and the military are becoming unrecognizable. Homosexuality has become the norm rather than the exception, and back on Earth there have been whole cycles of destruction and rebuilding. Even the language is different, and Mandella and Potter find they speak in an archaic dialect. They have no home to go to, the war continues on, and the powers-that-be are eager to capitalize on their knowledge as experienced combat officers. And in the interest of people who haven’t yet read the book, I will leave my summary here and the ending unspoiled, with encouragement to go out and find a copy.

The Forever War is carefully crafted and well researched. Haldeman’s training in astronomy is strongly in evidence, and consistent with the thinking in the field at the time the book was written. The conditions we expect to find in the extreme cold of outer planets are accurately described. The armored fighting suits are presented with capabilities that feel realistic. The spaceships and their maneuvers are portrayed in a scientific manner (although it always breaks my heart to read older books that assume capabilities for space travel would advance, rather than collapse at the end of the Apollo program). Medical scenes feel true to life, and the research that went into writing them is in clear evidence. The impact of relativity and time dilation is well developed, and has a huge impact on the plot. The characters feel real, and by the end of the book the reader will care about their fates. The prose is crisp, direct and rich with details, yet those details are presented organically, and they never bog down the narrative. This book is not only one of the best military science fiction books ever written, but is one of the finest works of modern American literature.

Final Thoughts

The Forever War is a modern classic. It presents an unflinching view of the horrors of war, and the corrosive effect war can have on a society. It deals with themes of loss and alienation that are often overlooked by other writers of military fiction, whose focus is bravery and glory. The U.S. military has been waging war on terrorists since the turn of the century. Like Mandella and Potter, we have veterans who have served in deployment after deployment, finding civil society increasingly disorienting each time they return. At a time when we are engaged in another type of Forever War, this book gives us a lot to think about.

The Forever War is a modern classic. It presents an unflinching view of the horrors of war, and the corrosive effect war can have on a society. It deals with themes of loss and alienation that are often overlooked by other writers of military fiction, whose focus is bravery and glory. The U.S. military has been waging war on terrorists since the turn of the century. Like Mandella and Potter, we have veterans who have served in deployment after deployment, finding civil society increasingly disorienting each time they return. At a time when we are engaged in another type of Forever War, this book gives us a lot to think about.

So if you haven’t read this lightning bolt of a book, go out and find a copy. And if you have read it, I’d like to hear from you. When did you first read it, and what was your reaction? How do you feel about the themes it presents, and the way those themes are handled? And have your responses to the novel changed at all, over time?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for five decades, especially science fiction that deals with military matters, exploration and adventure. He is also a retired reserve officer with a background in military history and strategy